This website uses cookies. By using this website, you agree to our Cookie Policy.

In early 2022, the ESG ratings industry attracted attention when electric vehicle manufacturer Tesla Inc. was dropped from the S&P 500 ESG Index. Explaining its decision, S&P cited perceived deficiencies in many ESG areas, including Tesla’s lack of an internal low carbon strategy for reporting and reducing carbon emissions, insufficient codes of business conduct, claims of racial discrimination and poor working conditions at a California factory, and poor handling of a federal investigation into deaths and injuries linked to Tesla’s autopilot vehicles.1 Tesla was not dropped from other comparable ESG indexes.2

The differing treatment of Tesla from an ESG rating perspective highlights several realities about the ESG rating industry: first, the fact that ESG ratings providers use different ranking methodologies often results in assigning divergent rankings to the same company. Second, lumping all of “E” and “S” together—or, at times, all of the different issues within each of these categories—can obscure the reason for a particular company’s ESG rating. The at times low correlation among ranking scores, the lack of granular information as to the basis of the rating, and, more generally, concerns around the transparency of ratings processes have led some to question the value, or how to best make use, of ESG ratings. Confusion and controversy can exist even with respect to ratings conferred by a single ESG ratings provider. Industry commentators, for instance, have raised questions regarding the S&P 500 ESG Index’s inclusion of companies such as ExxonMobil and McDonald’s (the latter of which generated more greenhouse gases than Portugal or Hungary in 2019) and the exclusion of Tesla and technology companies such as Meta.3

A major contributor to this situation is that ESG ratings providers use a variety of sources of data, methodologies, and formulae to arrive at their ultimate ESG scores. They present their data using different scales—some using letter rankings with others providing numerical scores—causing difficulty when trying to perform one-to-one comparisons between ESG ratings providers. Some ratings providers rely solely on publicly available information as their source data, whereas others rely on questionnaires and feedback from companies directly, which may include material information not otherwise available to the public, in addition to information that is publicly available. A 2021 EY survey revealed that 46% of asset managers viewed the lack of daily information to be a limitation on the value of ESG data,4 however few ratings providers update their data on a day-to-day basis. These different methodologies and approaches have led to poor correlation among ESG ratings.5 One consequence is even greater proliferation of rankings: a 2021 report found that 20 of the 50 largest global asset managers use data from four or more ESG ratings providers in order to make informed decisions about their sustainable finance products.6 The same report found that 30 of the same asset managers have developed their own proprietary internal ESG ratings systems.7

Further, there is growing recognition that most ratings do not assess companies’ sustainability profiles, but instead are based on the impact of climate change on a company’s anticipated financial performance: “[R]atings don’t measure a company’s impact on the Earth and society. In fact, they gauge the opposite: the potential impact of the world on the company and its shareholders.”8 If an ESG ratings provider concludes that “climate change neither poses a risk nor offers ‘opportunities’ to the company’s bottom line,” it may issue a higher ESG rating that is not necessarily reflective of that company’s sustainability efforts.9

As discussed in our article “Climate Risk Is Investment Risk”: The Asset Management Industry Confronts The Challenges and Opportunities Presented By Climate Change Transition, asset managers face challenges when assessing the sustainability of their investments and then disclosing those characteristics to investors due, in part, to the lack of coherent ESG ratings based on consistent and reliable criteria and methodologies. There are currently more than 600 ESG standards and frameworks, data providers, and ratings and rankings, provided by a mix of established credit ratings agencies and data vendors, along with niche providers. At present, there is very little consistency across ESG ratings providers and no established industry norms relating to disclosure, measurement, transparency and quality. This poses challenges to investors and fund managers seeking ESG investment opportunities and, at worst, raises concerns that the lack of consistency may facilitate greenwashing. These challenges are only likely to increase as ESG assets are estimated to reach $53 trillion by 202510 and risk outstripping the capabilities of existing ratings providers. In this area, many investors prefer active investment strategies and “want managers to use active security selection to uncover ESG opportunities and active ownership to engage and influence investee companies.”11 One commentator estimates there are approximately 240 ESG-focused ETFs in the U.S. alone, and over 500 ESG-focused ETFs in Europe.12

Regulators in the U.S., UK, and EU recognize this as an important issue and are starting to develop rules in this area. In the U.S., the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) is pushing to standardize climate-related disclosures by public companies which, it is hoped, will have a positive knock-on impact on the accuracy of ESG ratings.13 In the EU, the European Securities and Market Authority (“ESMA”) is considering increased regulation of the ESG ratings sector.14 In the UK, the Financial Conduct Authority (“FCA”) has opined that low correlation among ESG ratings is not, in itself, harmful, as long as ratings providers are transparent about their methodology and the data they use and have robust governance processes.15 The Board of the International Organization of Securities Commissions (“IOSCO”) has also published recommendations for ESG ratings providers.16 Industry bodies such as the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation recently launched the International Sustainability Standards Board, aimed at delivering “a comprehensive global baseline of sustainability-related disclosure standards that provide investors and other capital market participants with information about companies’ sustainability-related risks and opportunities to help them make informed decisions.”17 The common theme across regulators and industry bodies is a push toward increased transparency. This approach is backed by research that transparent disclosure standards and publicly accessible data is the solution to fight the “noise” from conflicting ESG ratings.18

This article contains a detailed discussion of these issues. It begins by explaining the purpose of ESG ratings and outlining some common categories of information and data that are considered when calculating ESG ratings. To highlight the different approaches in the current market, the article goes on to summarize the methodologies applied by some of the leading ESG ratings providers. This is followed by a discussion on why ratings for the same company differ among different providers and how the ratings are used by investors and asset managers. A summary of the current regulatory initiatives in various jurisdictions, including the U.S., the UK and the EU, is provided and the article concludes with some key takeaways.

ESG ratings are likely to remain in the spotlight given their importance for investors, issuers and policymakers. It remains to be seen whether the current ESG ratings ecosystem can be simplified through regulatory measures or broader market consensus. More consistency would certainly benefit investors and companies focused on sustainable initiatives. Another approach might be for ratings providers to unbundle and separately rank companies according to the “E,” “S,” and “G” (some ratings providers, such as S&P, do currently provide such disaggregated information), thereby providing investors with more targeted assessments and therefore more useful information. After all, different investors may, for instance, place different weight or value on a company’s ability to manage climate change transition versus its workplace environment. One commentator has observed, for example, that certain technology companies score highly in ESG ratings due to low greenhouse gas emissions despite questionable labor and misinformation policies (an example of environmental factors giving a company a high ESG score despite alleged poor performance on social factors.)19 One proffered reason is that social risk factors and issues have been poorly defined so far.20 Asset managers may be able to derive the greatest value from ratings providers that present “E,” “S,” and “G” scores (or present even more granular information on an issue-specific basis with the “E” and “S” categories) individually and transparently so that they can provide the best solutions for their clients’ specific needs.

Ultimately, however, the current polyphony of approaches is reflective of: (1) the wide range of information to consider regarding a company’s ESG profile; (2) the lack of consensus on how to assess that information; and (3) divergent views on what constitutes “good” and “beneficial” in the broader ESG market. Only by offering greater transparency regarding the inputs to their rankings and how those inputs are assessed and weighed, can ESG ratings providers offer consumers of that information a basis to make informed decisions as to how to effectively utilize the ratings.

Each of these subjects is discussed in detail below. Our takeaways include:

A. Ratings Divergence: In its response to the EU’s consultation on a renewed sustainable finance strategy, ESMA cited one study finding that ESG ratings are 60% correlated, compared to a 99% correlation for credit ratings from the top three credit rating agencies. The lack of standardized ESG disclosures or weighting of ESG factors coupled with the grouping (and subjective weighting) of all ESG issues drives this divergence, which in turn causes market participants to question the accuracy and comparability of ratings by any ESG provider. However, while no doubt helpful, increased ESG disclosure alone seems unlikely to alleviate all the challenges associated with using ESG ratings. One Harvard study found that increased ESG disclosures were correlated with greater ESG rating disagreement—“[b]y moving from the 25th to the 75th percentile in terms of ESG disclosure, firms saw the spread between their best and worst ESG scores widen by as much as 31 percent.”21 Because each ESG ratings provider selects its own variables, measures each variable using its own method, and weighs each variable to add up to its score differently, transparency regarding methods and input will not lead to ratings convergence.22 That, in turn, calsl into question the utility of any provider’s rating, which is intended as a short-hand, simple way to assess a particular company’s sustainability characteristics. It follows that the current state of play, where ratings are only truly meaningful if the consumer takes the time to dig into the rating provider’s approach, will persist until there is an industry or regulatory consensus regarding ESG rating methodology.23

B. Tension Between the E, the S, and the G Calls for Distinct Scores for Each: As illustrated by the ESG ratings of Tesla, a company may have a positive environmental impact but a poor work culture. Though investors may care about both when reviewing a company’s ESG score, a poor “S” rating may obscure a positive “E” rating in an overall ESG rating and, thus, mislead investors or at least deprive them of valuable information regarding a company’s sustainability efforts. To resolve this issue, ESG ratings providers should consider assigning subscores for the “E,” “S,” and “G,” or even to discrete issues within each category.

C. Investors Should Not Rely on ESG Ratings as a Sole Indicator: As many asset managers already do, investors should look to ESG ratings—from multiple providers—as a starting point to guide further diligence. The divergence in ratings and variability in definitions renders ESG ratings unreliable as a sole mechanism to judge potential ESG investments.

D. Potential Litigation: Because ESG ratings can vary significantly, enforcement actions or litigation are possible. An asset manager that relies on a particular ESG provider to assess the sustainability of its portfolio may be accused by regulators or clients of “greenwashing” to the extent that other providers assign lower ratings to those same companies. Likewise, a company’s employees who participate in company-sponsored retirement vehicles could claim that the employer misrepresented the sustainability of investment offerings based on the divergence among ESG rating providers.

E. Conflicts of Interest: Another area of concern to regulators and other market participants is that ESG ratings providers often provide other services, such as ESG consulting services. The risk that a ratings provider might provide a better rating in order to win other business from a particular company raises a number of challenges, including the quality of disclosure regarding the issue, how a company or asset manager should deal with the potential conflict if it utilizes that provider’s ratings, and the concern that such conflicts may lead to industry regulation.

F. Ratings Bias: Consumers of ESG ratings should consider the possibility of unintended ratings bias being injected into the process. As noted above, RepRisk attempts to account for a large company bias, which it characterizes as negatively affecting large cap companies because they receive greater media attention. However, ESMA has pointed to a bias in favor of large caps, which have the resources to respond to provider surveys and generally address ESG perceptions in the marketplace. And, in fact, large cap companies on average receive higher ESG ratings.24 Another potential bias, for example, could be based on geography—European companies on average score higher than U.S. companies, while companies in emerging markets generally receive lower scores.25

I. WHAT ARE ESG RATINGS

ESG ratings aim to measure a company’s or portfolio’s long-term exposure to environmental, social and governance risk factors.26 Ultimately, they attempt to quantify and standardize the financial risks that ESG factors pose to companies and, by extension, shareholders.27 They are designed to be used for two purposes: first, “by individual investors and fund managers to guide investment strategies by understanding potential sustainability risks to business performance” and second, “as an internal benchmarking tool to help improve sustainability performance and for potential public relations opportunities.”28 Issues arise when different ratings providers implement different methodologies and source different data to calculate their ratings, leading to what one group of researchers refers to as “noise.”29

It also is noteworthy that, by and large, ESG ratings only measure one aspect of what European regulators refer to as “double materiality,” which reflects a view that information can be important and should be disclosed if related to a company’s financial performance (also known as the “outside in” perspective) or to the sustainability impact of a company on society and the planet (“inside out” perspective).30 The concept of double materiality is incorporated in the EU’s various sustainability reporting directives, such as the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation.31 While it is not clear whether U.S. regulators will expressly adopt the concept, it is not a stretch to conclude that investors may consider information material under a traditional TSC Industries standard even if it relates to the “inside out” perspective (i.e., a company that currently is successfully managing climate transition may nonetheless suffer material harm, such as loss of customers, harm to reputation, and regulatory scrutiny, due to its negative impact on the external climate).32 The failure of most ESG ratings providers to take such information into account is a significant shortcoming in the ratings landscape.

II. FACTORS & WEIGHTING PRESENTATIONS, SUMMARY DESCRIPTIONS OF METHODOLOGIES OVERVIEW & GRAPHICS OF LEADING RATINGS PROVIDERS

As described above, there is “noise” surrounding the different methodologies utilized by data ratings providers in computing ESG scores. In this section, we explore the approaches employed by five leading ESG ratings providers.33 This is followed with a summary table outlining some of the key aspects of the methodologies employed by each provider.

A. MSCI ESG Ratings

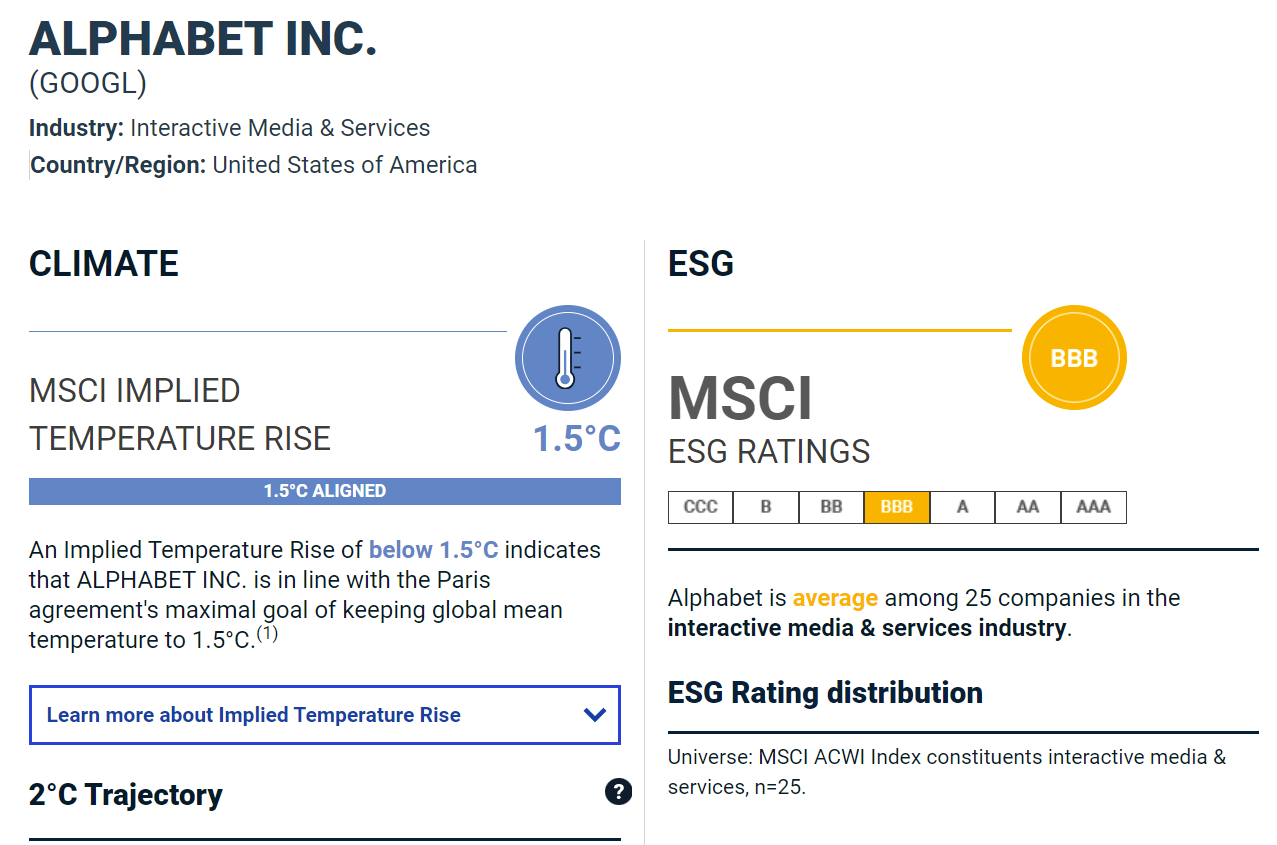

MSCI is a global provider of equity, fixed income, real estate indexes, multi-asset portfolio analysis tools, ESG and climate products. It offers ESG ratings for over 2,900 companies using 35 key “issues” that it determines to be material for each industry.34 It sources data from third-party academic, government, and NGO datasets, public disclosures by companies, and government media, NGO, and other shareholder databases.35 While MSCI does send data requests to companies directly, it does not consider in its analysis any data that is not otherwise publicly available.36 It publishes one overall rating for each company, calculating and normalizing the weighted average of scores for each applicable key issue against industry peers. Each environmental and social key issue contributes between 5–30% (these are weighted scores) of the final ESG rating, while all the governance issues combined contribute at least 33% to the final ESG rating.37 The key issues examine a company’s exposure to and management of both risks and opportunities associated with climate transition and other ESG-related issues.38 Environmental and social key issues include carbon emissions, raw material sourcing, packaging material and waste, labor management, privacy and data security, and product safety and quality. Governance key issues include ownership and control, matters relating to the board of directors, business ethics, and tax transparency. The final rating is only provided after a quality check by an ESG Ratings Review Committee, which “reviews the selection of key issues, assignment of weights, treatment of company-specific issues, rating changes and rating distribution before giving final approval.”39 After incorporating any “committee-level overrides,” i.e., situations where MSCI determines to override the data based on a qualitative assessment,40 MSCI rates a company on a scale of AAA (the best) to CCC (the worst).41 This climate rating ultimately aims to provide a measure of “a company’s resilience to long-term, financially relevant ESG risks,”42 reflecting the outside-in perspective described above. For example, Alphabet Inc.’s MSCI data is produced in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Alphabet Inc. ESG Rating from MSCI

B. Refinitiv ESG Scores

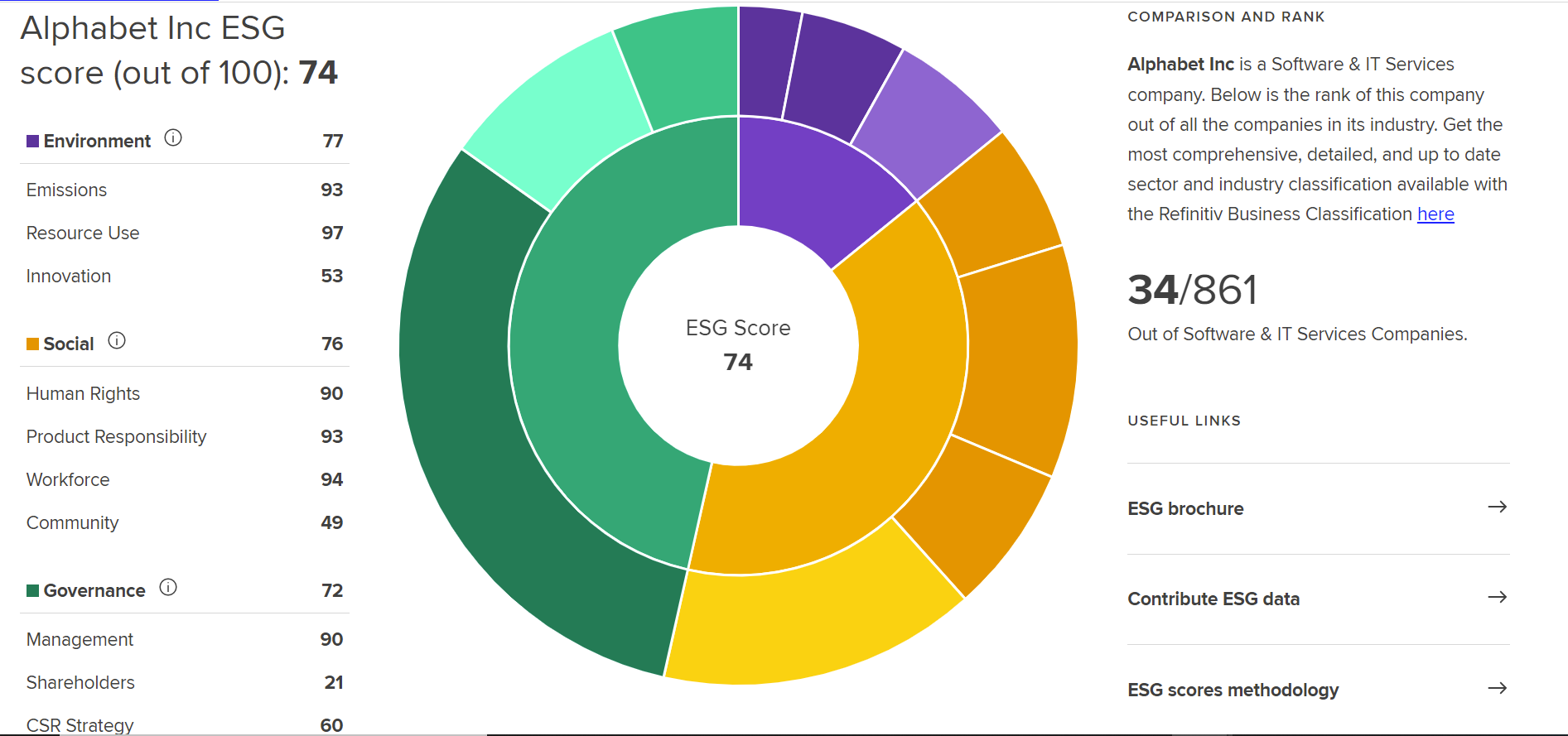

Refinitiv, a subsidiary of the London Stock Exchange, is a leading provider of financial market data. It provides two scores for over 11,800 companies globally: (1) an ESG score that evaluates a company’s performance of ESG factors—measured relative to other companies in the same sector—and capacity to address those ESG factors; and (2) an ESGC score that discounts from the ESG score to account for any material ESG controversies.43 Data is collected for over 630 ESG measures from publicly available sources such as companies’ annual reports, websites, and ESG disclosures, NGO websites, public filings, and news sources.44 ESG measures include a company’s use of resources like water and energy, its commitment to reducing emissions, and the “effectiveness in terms of respecting fundamental human rights conventions,” to name a few.45 The data is audited and updated weekly.46 Refinitiv groups the ESG measures into 10 categories (listed below in Figure 2) in which companies are scored comparatively, based on percentile rank.47 The 10 category scores are then sorted into environmental, social and governance pillar scores, with each pillar score reflecting the relative sum of the category weights normalized to a percentage between 0 and 100.48 From these pillar scores, the ESG score is calculated. Separately, an ESG controversies score is calculated using 23 ESG controversy topics, while addressing the market cap bias that results from the fact that large-cap companies attract relatively greater media attention and scrutiny (although the FCA in its 2021 ESG disclosure consultation—discussed below—posited that mid- and small-sized companies are penalized by ratings providers that request company survey responses on the theory that they have less resources to devote to actually completing the survey and correcting misimpressions on the part of the provider).49 Refinitiv calculates the ESGC score by discounting, as a weighted average, the ESG controversies score from the final ESG score.50 A company’s ESG score is presented both as a numerical score out of 100, as well as ranked out of all other companies in the industry. Refinitiv’s scores are aimed at helping asset managers assess ESG risks and opportunities in investment portfolios, focusing on company valuation, risk management, and regulatory compliance51—i.e., adopting the outside-in financial perspective described above. For example, Alphabet Inc.’s Refinitiv data is produced in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Alphabet Inc. ESG Score52 from Refinitiv

C. Sustainalytics Risk Ratings

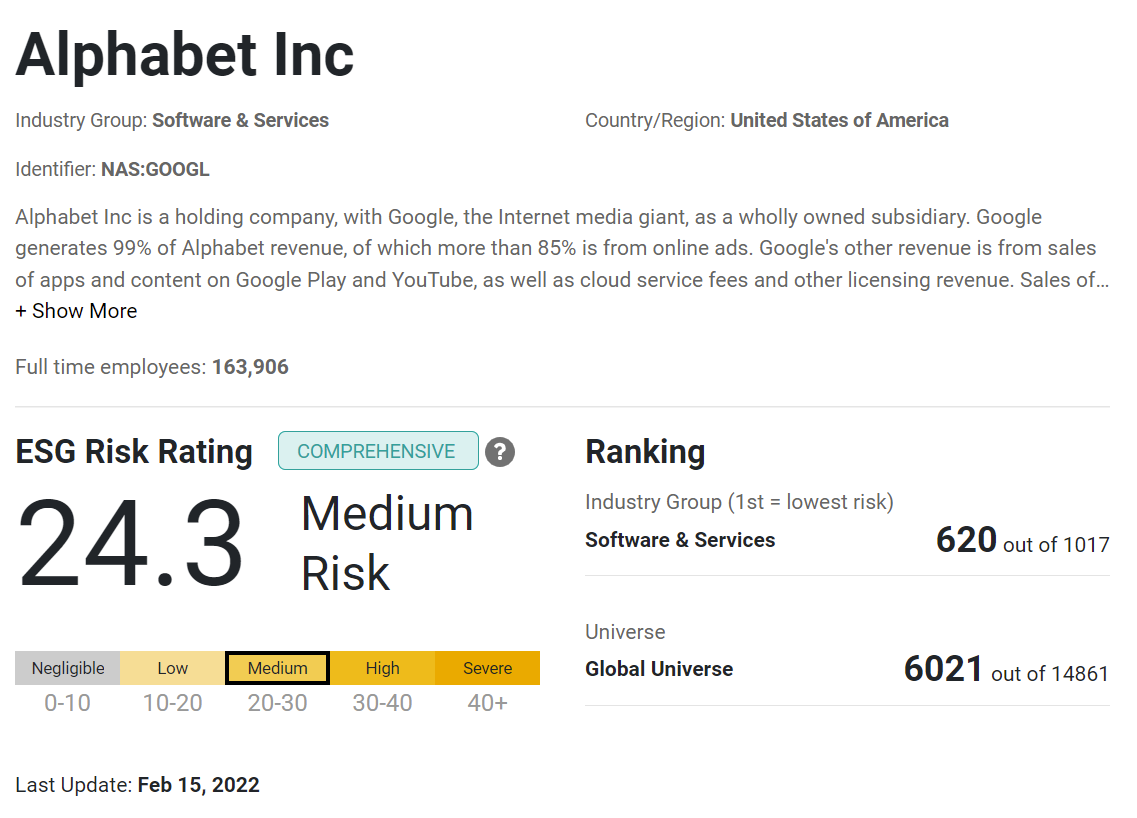

Sustainalytics, owned by Morningstar, calculates the magnitude of a company’s unmanaged ESG risks—material ESG risks that are (1) unmanageable and not even in theory capable of being addressed by the company’s initiatives and (2) potentially manageable but not currently sufficiently managed by the company—as a measure of its economic value, reflecting the outside-in perspective.53 It gathers data from public disclosures, media analyses, and NGO reports, as well as direct feedback from companies.54 The overall ESG risk rating is based on assessment in three main areas: corporate governance, material ESG issues, and idiosyncratic ESG issues.55 The corporate governance “block” applies to all companies and contributes roughly 20% to the overall risk rating.56 Material ESG issues are those that affect all companies in a particular industry in a predictable manner and “require a common set of management initiatives or a similar type of oversight.”57 On the other hand, idiosyncratic ESG issues are those unrelated to a particular industry, such as event-driven scandals that affect a specific company.58 Sustainalytics measures both exposure to ESG risks and management of that exposure. First, Sustainalytics calculates the average exposure to a material ESG issue within each subindustry in which the company operates.59 The subindustry exposure assessments are conducted annually.60 Second, a beta score representing the degree to which a specific company’s exposure to that issue deviates from the subindustry average is calculated.61 The company’s exposure is calculated by multiplying the beta score by the subindustry exposure score.62 Third, Sustainalytics also measures manageable risk factors for each subindustry, which represents “the share of exposure to a material ESG issue that is deemed to be (at least theoretically) manageable by the company.”63 Fourth, the unmanaged risk for each material ESG issue is calculated by subtracting the managed risk from the company’s exposure score. Finally, a company’s overall ESG risk rating score is tabulated as the sum of the unmanaged risk scores for each individual material ESG issue confronting the company.64 The risk ratings score is presented alongside a risk categorization. For example, the Sustainalytics report for Alphabet Inc. is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Alphabet Inc. ESG Risk Rating from Sustainalytics

D. RepRisk Ratings

Based in Switzerland, RepRisk maintains the world’s largest database of ESG risk research, with information from or concerning over 200,000 public and private companies, over 50,000 infrastructure projects, over 25,000 NGOs, and over 19,000 governmental bodies.65 It also sources and updates data daily from over 100,000 public sources and stakeholders, such as news media, social media, blogs, government bodies, and think tanks, in 23 languages and ranging from the international to local level.66 The research is focused on 28 ESG issues67 and 73 ESG topics.68 RepRisk’s 28 issues are the core of its research process, with each selected and defined pursuant to international ESG and business conduct standards—i.e., World Bank Group Environmental, Health, and Safety Guidelines and the UN Global Compact.69 The 73 topics are extensions of the issues and are more thematic, with each topic relating back to one or more issues. For example, the “epidemics/pandemics” topic relates to nine separate issues: anti-competitive practices; corruption, bribery, extortion, and money laundering; fraud; freedom of association and collective bargaining; impacts on communities; misleading communication; poor employment conditions; products (health and environmental issues); and occupational health and safety issues.70 Unlike other ratings methodologies, RepRisk uses issue- and event-driven approaches, instead of a company-specific approach. In that vein, every risk incident affecting an industry that flags one of the 101 ESG factors RepRisk evaluates is analyzed and quantified.71 Risks are calibrated both generally, industry-wide, as well as specifically as to a company or country-sector.72 Based on its methodology, RepRisk publishes three different results: (1) a RepRisk Index score, from zero (lowest) to 100 (highest), that quantifies reputational risk exposure for the ESG issues; (2) a RepRisk Rating, from AAA (best) to D (worst), “that facilitates corporate benchmarking against the peer group and sector of a company, as well as integration of ESG and business conduct risks into business processes;” and (3) a United Nations Global Compact Violator Flag that identifies companies that have a high risk or potential risk of violating one or more of the ten UN Global Compact principles.73 A company’s rating is dependent on the risks and index as well as the company’s country-specific ESG risk and industry-specific ESG risk.74 RepRisk’s ESG ratings are proprietary and therefore we are unable to include an example of the data it provides.75

E. S&P Global ESG Scores

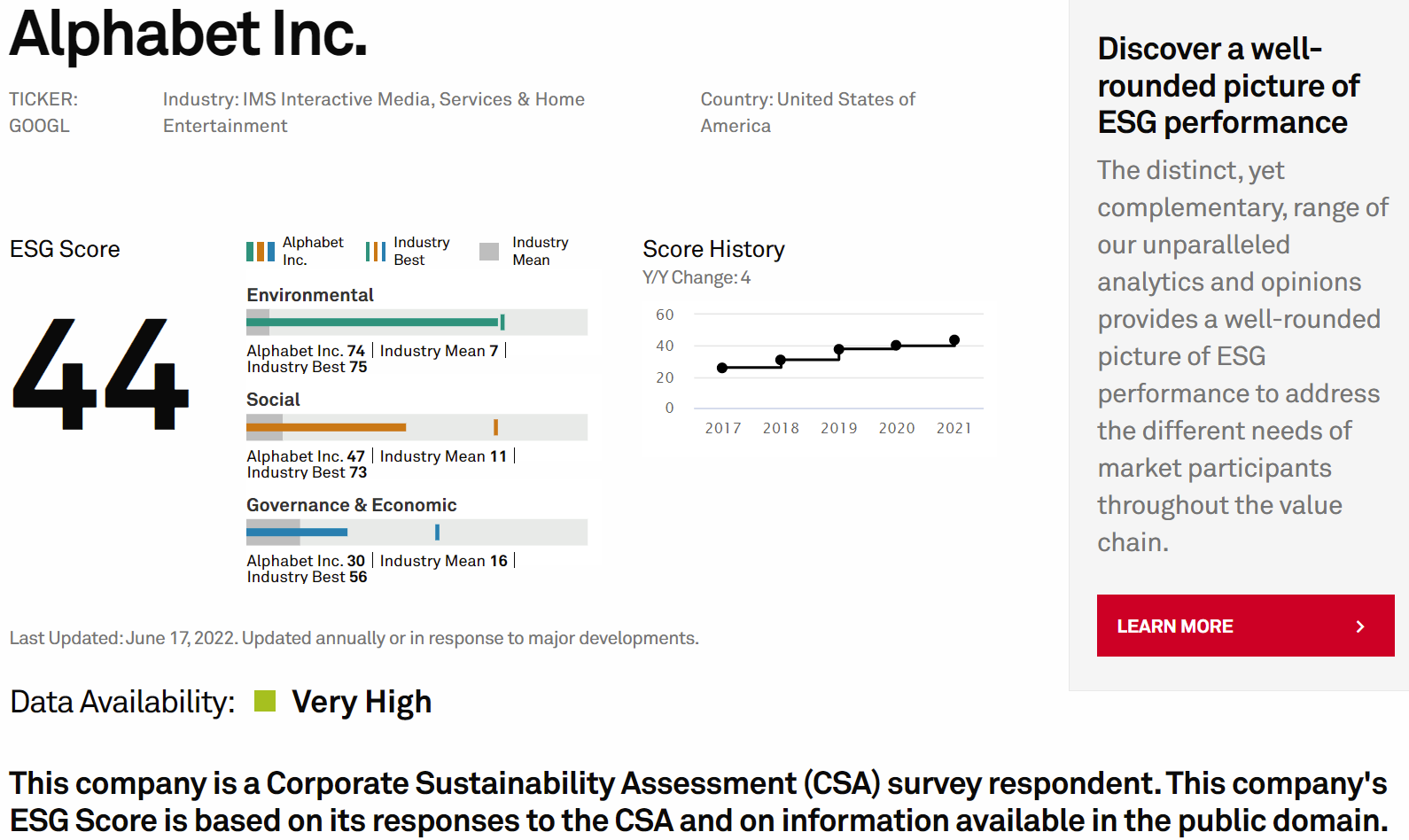

S&P Global covers 8,000 companies worldwide encompassing 90% of global market capitalization.76 It analyzes many of the same subindustries as MSCI because both utilize the Global Industry Classification System, a joint product developed by MSCI and S&P that has been providing classification across industry sectors since 1999.77 The S&P Global ESG Scores “measure companies’ exposure to and performance on key ESG risks and opportunities, the quality and completeness of their public disclosures, and their awareness of emerging but underreported ESG issues.”78 Data is sourced directly from publicly listed companies using 61 industry-specific questionnaires—the Corporate Sustainability Assessment (“CSA”)—that request data and supporting evidence beyond that available in public disclosures.79 Analysts complete the assessment questionnaires for companies that do not respond to the invitations.80 Each question receives a score using pre-defined scoring frameworks, which then aggregates to criteria-level scores that reflect the most material ESG themes for each subindustry. Criteria-level scores combine into standalone E, S, and G “Dimension Scores,” which are then further combined into a single ESG score for each company.81 S&P Global uses RepRisk to monitor daily corporate controversies and may downgrade a company’s ESG score if the controversy is sufficiently severe.82 All companies are evaluated annually using the CSA and the data underlying the scores is updated monthly.83 For example, a portion of the S&P Global report for Alphabet Inc. is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Alphabet Inc. ESG Score from S&P Global

F. Summary of Leading ESG Ratings Providers

As shown above in Sections II.A–E, ratings providers differ in the sources of information utilized, the methodologies that they apply to calculate their ratings as well as in the ultimate presentation of their ratings. This summary table outlines some of the key aspects of the methodologies.

|

|

MSCI |

Refinitiv |

Sustainalytics |

RepRisk |

S&P Global |

|

Data Sources |

Public disclosures, government databases, stakeholder databases, third-party datasets |

Public disclosures, NGO reports, media analysis |

Public disclosures, NGO reports, media analysis |

Media analysis, social media, government reports, think tanks |

Public and non-public information provided by companies, or public information surveyed by analysts |

|

Company Involvement84 |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Methodology |

Examines 35 key issues across three “pillars” and ten “themes” |

630+ measures evaluated over 10 categories, with a separate ESGC score assessing 23 controversy topics |

Sum of unmanaged risk85 scores for industry-specific material ESG issues, including corporate governance and idiosyncratic ESG issues86 |

Calibration of risks based on daily reports87 focused on 28 ESG issues and 73 additional ESG “hot topics” |

Questionnaires completed by companies and scored and weighed into E, S, and G standalone scores as well as overall ESG score |

|

Rating Scale |

AAA to CCC |

Numerical score out of 100 as well as separate ESGC score |

Numerical score of 100 as well as industry-based comparison |

AAA to D |

Numerical score out of 100 |

|

Publicly Available |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Updates |

Weekly updates and annual company-level review |

Weekly updates |

Annual updates |

Daily updates |

Daily assessment of controversies with annual company-level review |

III. ESG RATINGS IN THE ASSET MANAGEMENT INDUSTRY

ESG ratings are available to and considered by various type of participants in all industry sectors, including government regulators, companies, and individual investors. Asset managers in particular may have reason to rely on ESG ratings, whether for purposes of assessing potential sustainability risks to business performance, or in order to avoid greenwashing the sustainability characteristics of their portfolios.88 ESG ratings may qualify or disqualify a particular security from an asset manager’s portfolio if the manager is working within a defined ESG mandate.

How asset managers utilize ESG ratings differs based on each firm’s objectives as well as internal resources and expertise.89 In its fact-finding exercise conducted to gain an understanding of the significant role played by ESG ratings and data in financial markets around the world, IOSCO90 observed a wide variation as to how asset and fund managers consume and use the information provided by ESG ratings.91 Specifically, the study revealed a broad range of uses for ESG ratings, including to:

- “integrate ESG factors in their investment process, manage sustainability exposure and/or opportunities of their investment portfolio, or develop and oversee sustainable products”;

- “use[] ratings to guide [their] stakeholder engagement strategy with invested companies or produce ESG reports for clients”; or

- “monitor external asset managers as a trustee by assessing their exposure to ESG, and more specifically, climate risks.”92

But a majority of participants declined to indicate how ESG ratings are incorporated into investment decision-making.93 Certain respondents indicated that they do not incorporate ESG ratings into all of their investment decisions but instead, at times use them to “reinforce internal analyses and investment decisions by helping to identify risks and opportunities.”94 For many firms, looking to the ESG rating is only one step in a significantly broader research process.95

Adding yet another nuance to ESG rating consumption, “several [firms] have developed their own KPIs [key performance indicators], tools, processes and scores to fully evaluate corporate ESG performance and ‘find [their] own answers.’”96 Large asset managers may seek out ESG providers that provide the broadest possible coverage of sectors and geography because they can incorporate that data into their own tools, processes, and scores. This enables them to identify key ESG factors in each sector and use their internal resources to conduct further diligence. For instance, BlackRock uses certain external ESG ratings to contribute to three main themes driving its ESG integration efforts: investment processes, material insights, and transparency.97 The firm creates its own internal ESG ratings based on the data provided by third parties and its own set of analytic tools. Blackrock’s actively-managed funds and advisory strategies are ESG-integrated, meaning that portfolio managers are accountable for managing exposure to material ESG risks, and investment teams are required to demonstrate how they incorporate ESG information into their investment strategies.98 Similarly, State Street developed an internal ESG scoring system based on external ESG ratings and other data from third-party providers. It then uses internal scores to inform investment decisions and advise both companies and investors.99

IV. REGULATION OF ESG RATINGS

There is currently little alignment among regulators on an appropriate or effective approach to regulate ESG ratings. Current approaches focus on the transparency of rating methodologies, improved reliability and accuracy, the adoption of disclosure standards or a combination of these elements.

A. Regulation of ratings (Global)

United Kingdom

In 2021, the FCA published a Consultation Paper[100] inviting views on whether the regulation of ESG ratings providers should be brought within the FCA’s regulatory authority or, alternatively, whether these service providers should simply be encouraged to adopt a voluntary Best Practice Code.101 In its corresponding Feedback Statement FS22/4102, the FCA reported seeing a clear rationale for the regulation of ESG data and rating providers.103 The FCA further explained that, “as industry participants more fully integrate ESG into their activities and expand their ESG‑focused product offerings, they are increasingly reliant on third‑party ESG data and rating services. These services are increasingly embedded within investment processes (including mandates and benchmark indices), directly influencing capital allocation.”104 In order to protect the integrity of financial markets and harm to investors, the FCA advocates for ESG data and rating services to be transparent, well‑governed, independent, objective, and based on reliable and systematic methodologies and processes. Further, where such services aim to measure specific ESG attributes, users should be able to understand their purpose and access sufficient information in order to assess whether their outputs are fit for their intended purpose.105

The Feedback Statement also sets out that the FCA will coordinate its regulatory focus with IOSCO’s recommendations so as to ensure international coordination. The potential future direction of travel in respect of ESG data and ratings providers is to “develop and consult on a proportionate and effective regulatory regime with a focus on outcomes in areas highlighted in IOSCO’s recommendations.”106 The FCA also states, however, that “given the lead time before any such regime could come into force [it] would, in the interim, convene, support and encourage industry participants to develop and follow a voluntary code of conduct. Such a voluntary code could potentially continue to apply for ESG data and rating providers that fall outside the scope of any future regulatory regime.”107 Nevertheless, industry participants are starting to develop their own frameworks governing sustainable investing, though none has yet been made available. Further, in July 2022, Japan’s Financial Services Agency issued a draft Code of Conduct for ESG ratings providers;108 the FCA has stated that it strongly supports an international coordinated approach, coordinating as far as possible with other jurisdictions on the design of any regulatory approach or voluntary Code of Conduct, and the Japanese draft therefore provides a possible indication of what a UK voluntary Code of Conduct might look like.109

Recently, the FCA has focused on the transparency of disclosure rather than setting out how ESG ratings providers should apply their rating methodologies. The purpose of disclosure is to enable informed investor decision-making while periodic reporting aims to reflect a fund’s progress against its ESG objectives.110 The FCA’s Consultation Paper acknowledged that ESG ratings are highly influential because of how broadly they are used by a range of market participants: for investment purposes; by companies to benchmark their own performance; and by investors who are using ESG ratings in a fairly simplistic way to determine whether a company is ‘good’ or ‘bad’.111 Nonetheless, the FCA does not consider a low correlation among different providers’ ESG ratings in and of itself as a source of harm so long as such providers:

- are transparent about their methodology and information and data inputs;

- determine their outputs by applying systematic processes and sound systems and controls;

- identify and manager conflicts of interest; and

- operate with robust governance.112

The FCA is expected to provide a detailed pronouncement on its approach to ESG-related regulation in 2023 following this year’s consultation process.

European Union

In February 2022, the European Commission (“EC”) updated its sustainable finance strategy demonstrating active engagement with regards to recommendations for ESG rating and data providers.113

For ESG ratings providers, the EC suggested114 the introduction of conflict of interest rules, minimum disclosure requirements for ratings methodology and a centralized EU registration system for providers, rather than imposing mandatory ratings criteria aimed at making ratings more standardized and comparable. Further, the EC has considered whether to make credit rating agencies disclose the impact or absence of ESG factors within their ratings and an explicit requirement to take ESG factors into account where relevant. Currently, credit rating agencies do not incorporate assessments of long-term ESG factors such as climate pledges and climate risks within credit ratings on the basis that such factors do not have immediate credit implications.

Subsequently, ESMA, the European Union’s financial markets supervisory authority, called for written submissions in order to develop an understanding of the market for ESG rating providers active in the EU and gather the views of users and entities covered by ESG ratings. Publishing its results in June 2022,115 ESMA reported that the majority of users of ESG ratings contract for those products from several providers simultaneously, so as to increase coverage (either by asset class or geographically) in order to receive different types of assessments. Shortcomings identified by users included a lack of coverage of a specific industry or a type of entity and insufficient granularity of data. ESMA reported that complexity and lack of transparency around methodologies are cited as an issue. Further, users highlighted some degree of shortcoming in their interactions with ESG ratings providers, most notably with respect to transparency as to the basis for the rating, the timing of feedback, or the correction of errors.

As is the usual course, the EC will consider ESMA’s findings in its assessment of the need to introduce regulatory safeguards for ESG ratings products.

International standards

There are some interesting examples both within and outside the EU where funds are taking matters into their own hands in developing their own rating and scoring systems, prior to the publication of the disclosure recommendations by the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure: this includes Japanese insurance company, Nippon Life; Spanish insurer Mapfre; and Norges Bank Investment management, which runs Norway’s $1.4 trillion sovereign wealth fund. It is possible that when the IFRS’s International Sustainability Standards Board publishes its disclosure standards, these meet the growing demand for consistent, comparable and reliable corporate sustainability disclosures, which in turn places enough information in the public domain to allow investors to make more informed choices.

B. U.S. Regulation of ESG Ratings

While the SEC has not attempted to regulate ESG ratings providers directly, a proposed rule directed at asset managers could impact ESG ratings providers. In May 2022 the SEC proposed for comment new rules regarding asset manager disclosure.116 In order to combat inconsistencies among ESG ratings providers,117 the proposed rules would require: (1) disclosure of ESG strategies in prospectuses, annual reports, and advisor brochures; (2) a tabular disclosure approach that will more easily allow investors to compare among ESG funds; and (3) environmentally-focused funds to disclose the greenhouse gas emissions of their portfolio investments.118 According to the SEC, these requirements will encourage the increased transparency with respect to ESG ratings because asset managers will need to disclose how ESG ratings are used in their own ESG strategies—i.e., which ratings providers are used, why certain ratings providers were selected—as well as improve the quality and reliability of ESG ratings by promoting competition among ESG ratings providers.119 This proposed rule highlights the need for ESG ratings providers to be more transparent and standardize their data so that the asset managers that use the data they provide can comply with impending SEC reporting requirements.

Recently, Congress has joined the fray. On September 20, 2022, Senator Pat Toomey (R-Pa.), Ranking Member of the U.S. Senate Banking Committee, brought attention to the “noise” surrounding ESG ratings by sending letters to 12 ratings providers, including the five providers discussed above, MSCI, Refinitiv, Sustainalytics, RepRisk, and S&P Global. Senator Toomey stated his belief that many ratings providers “consider information that is not material or financially relevant under federal securities laws” and requests providers disclose information regarding “the specific E, S, and G factors measured and how those factors are weighed; how the firms determine the scope of industry sectors, including whether they employ analysts with sector-specific expertise; and reports intended to capture controversies faced by a company, such as pending litigation, negative press coverage, or shareholder resolutions.”120 The letters also request that ratings providers answer questions regarding the involvement of rated companies during ratings calculations, the veracity of data sources, the impact of political issues on ESG scores, and conflicts of interest. A senior advisor to Senator Toomey stated that “to date, [they have] received responses from several of the ratings providers. However, [they] have not published those responses nor the names of the companies that complied with the request.”

Interested in more information?

1 Margaret Dorn, The (Re)Balancing Act of the S&P 500 ESG Index, S&P Dow Jones Indices: Indexology Blog (May 17, 2022), https://www.indexologyblog.com/2022/05/17/the-rebalancing-act-of-the-sp-500-esg-index/.

2 Is Tesla ESG? Many funds own it. We say it's not for everyone, Bloomberg Professional Services: Bloomberg Intelligence (May 26, 2022), https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/blog/is-tesla-esg-many-funds-own-it-we-say-its-not-for-everyone/. For example, Tesla continued to be rated and ranked by Sustainalytics, a sustainability data and analytics firm owned by Morningstar, and also by Morgan Stanley’s unit Calvert Research and Management, where it remains included in various Calvert indexes. See Leslie Norton, This is Why Tesla’s ESG Rating Isn’t Great, Morningstar (May 22, 2022), https://www.morningstar.co.uk/uk/news/221629/this-is-why-teslas-esg-rating-isnt-great.aspx.

3 See, e.g., Lauren Foster, Tesla Got Dumped From an ESG Index. One Critic Calls the Move ‘A True Indictment’ of Sustainability Ratings, Barron’s (May 20, 2022), https://www.barrons.com/articles/tesla-sp-esg-index-sustainability-ratings-51653011864; Q.ai, Tesla Is Being Booted From The ESG Index, Forbes (May 20, 2022), https://www.forbes.com/sites/qai/2022/05/20/tesla-is-being-booted-from-the-esg-index/?sh=20de1d6b25d6; Tim Quinson, Tesla’s Removal From S&P Index Sparks Debate About ESG Ratings, Bloomberg (May 19, 2022), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-05-19/tesla-s-removal-from-s-p-index-sparks-debate-about-esg-ratings; Eloise Barry, Why Tesla CEO Elon Musk Is Calling ESG a ‘Scam’, TIME (May 25, 2022), https://time.com/6180638/tesla-esg-index-musk/; Leslie Norton, This is Why Tesla’s ESG Rating Isn’t Great, Morningstar (May 22, 2022), https://www.morningstar.co.uk/uk/news/221629/this-is-why-teslas-esg-rating-isnt-great.aspx; Tom Lyon, How Can a Sustainability Index Keep Exxon but Drop Tesla? A Look at ESG Ratings, The Fashion L. (June 15, 2022), https://www.thefashionlaw.com/how-can-a-sustainability-index-keep-exxon-but-drop-tesla-esg-ratings/; Cam Simpson, Akshat Rathi & Saijel Kishan, The ESG Mirage, Bloomberg (Dec. 10, 2021), https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2021-what-is-esg-investing-msci-ratings-focus-on-corporate-bottom-line/.

4 Anthony Kirby, Why data remains the biggest ESG investing challenge for asset managers, EY (July 5, 2021), https://www.ey.com/en_gl/financial-services-emeia/why-data-remains-the-biggest-esg-investing-challenge-for-asset-managers.

5 Kevin Prall, ESG Ratings: Navigating Through the Haze, CFA Institute (Aug. 10, 2021), https://blogs.cfainstitute.org/investor/2021/08/10/esg-ratings-navigating-through-the-haze/.

6 Garnet Roach, More than half of top 50 asset managers developing internal ESG ratings, IR Magazine (Mar. 8, 2021), https://www.irmagazine.com/buy-side/more-half-top-50-asset-managers-developing-internal-esg-ratings.

7 Id.

8 Simpson, Rathi & Kishan, supra note 3.

9 Id.

10 Adeline Diab & Gina Martin Adams, ESG assets may hit $53 trillion by 2025, a third of global AUM, Bloomberg: Bloomberg Intelligence (Feb. 23, 2021), https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/blog/esg-assets-may-hit-53-trillion-by-2025-a-third-of-global-aum/.

11 Jessica Ground, ESG Global Study 2022, Harv. L. Sch. F. On Corp. Governance (June 17, 2022), https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2022/06/17/esg-global-study-2022/.

12 Emma Boyde, ESG ETFs face perfect storm in the US, Fin. Times (Sep. 13, 2022), https://www.ft.com/content/768cda84-56fd-46ae-81a2-76fb0783e679.

13 Press Release, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, SEC Proposes Rules to Enhance and Standardize Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors (Mar. 21, 2022), https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2022-46; see also Jason Halper et al., SEC Proposes Climate-Related Changes to Regulation S-K and Regulation S-X, Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft LLP (Mar. 23, 2022), https://www.cadwalader.com/resources/clients-friends-memos/sec-proposes-climate-related-changes-to-regulation-s-k-and-regulation-s-x; Jason Halper et al., What Can Public Companies Do Now to Prepare for the SEC’s New Proposed Rules on Climate-Related Disclosures?, Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft LLP (Apr. 7, 2022), https://www.cadwalader.com/resources/clients-friends-memos/what-can-public-companies-do-now-to-prepare-for-the-secs-new-proposed-rules-on-climate-related-disclosures.

14 Press Release, European Securities and Markets Authority, ESMA Publishes Results of Its Call for Evidence on ESG Ratings (June 27, 2022), https://www.esma.europa.eu/press-news/esma-news/esma-publishes-results-its-call-evidence-esg-ratings/.

15 FS22/4: ESG integration in UK capital markets: Feedback to CP21/18, Fin. Conduct Authority 13 (June 2022), https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/feedback/fs22-4.pdf [hereinafter Feedback Statement, FCA].

16 Press Release, International Organization of Securities Commissions, IOSCO calls for oversight of ESG Ratings and Data Product Providers (Nov. 23, 2021), https://www.iosco.org/news/pdf/IOSCONEWS627.pdf.

17 International Sustainability Standards Board, IFRS, https://www.ifrs.org/groups/international-sustainability-standards-board/ (last visited Sept. 28, 2022); see also Simon Brooke, New International Sustainability Standards Board Aims to Unify ESG Metrics, Impactivate (Mar. 10, 2022), https://www.theimpactivate.com/new-international-sustainability-standards-board-aims-to-unify-esg-metrics/.

18 Florian Berg, Julian F. Kölbel, & Roberto Rigobon, Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings, 1 Rev. of Finance 4, 26-27 (May 23, 2022) (corrected proof), https://academic.oup.com/rof/advance-article/doi/10.1093/rof/rfac033/6590670 (using the term “noise” to describe divergent ratings); see also Tracy Mayor, Why ESG ratings vary so widely (and what you can do about it), MIT Sloan Sch. Mgmt. (Aug. 26, 2019), https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/why-esg-ratings-vary-so-widely-and-what-you-can-do-about-it; Dane Christensen, George Serafeim, & Anywhere Sikochi, Why is Corporate Virtue in the Eye of The Beholder? The Case of ESG Ratings, (Harv. Bus. Sch., Working Paper No. 20-084, 2021), https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/20-084_6c5b0248-d117-4049-baad-c0e1877eb537.pdf; Kristen Senz, What Does an ESG Score Really Say About a Company?, Harv. Bus. Sch. Working Knowledge (July 21, 2021), https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/what-does-an-esg-score-really-say-about-a-company.

19 Hans Taparia, The World May Be Better Off Without ESG Investing, Stan. Social Innovation Rev. (July 14, 2021), https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_world_may_be_better_off_without_esg_investing.

20 Michael Posner, ESG Investing Needs More Rigorous Standards To Evaluate Corporate Conduct, Forbes (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelposner/2022/02/01/esg-investing-needs-more-rigorous-standards-to-evaluate-corporate-conduct/?sh=47dd78857357; Jason Saul, Fixing the S in ESG, Stan. Social Innovation Rev. (Feb. 22, 2022), https://ssir.org/articles/entry/fixing_the_s_in_esg#.

21 Kristen Senz, What Does an ESG Score Really Say About a Company?, Harv. Bus. Sch. Working Knowledge (July 21, 2021), https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/what-does-an-esg-score-really-say-about-a-company.

22 Berg, Kölbel, & Rigobon, supra note 18.

23 Abraham Lioui, Sustainable Investing with ESG Rating Uncertainty, Harv. L. Sch. F. On Corp. Governance (July 5, 2022), https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2022/07/05/sustainable-investing-with-esg-rating-uncertainty/#more-147316.

24 Osman T. Akgun, Thomas J. Mudge III, & Blaine Townsend, How Company Size Bias in ESG Score Impacts the Small Cap Investor, 1 J. Impact & ESG Investing 1, 4, (2021), https://bailard.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Company-Size-Bias-in-ESG-Scores-Impacts-Small-Cap-JIESG-Bailard.pdf.

25 Garnet Roach, Inside the world of ESG ratings: Academic paper looks at multiple issues with process and outcomes, IR Mag. (Aug. 11, 2022), https://www.irmagazine.com/reporting/inside-world-esg-ratings-academic-paper-looks-multiple-issues-process-and-outcomes; see also David F. Larcker, Lukasz Pomorski, Brian Tayan, & Edward M. Watts, ESG Ratings: A Compass Without Directions 5–6 (Rock Ctr. for Corp. Governance Stan. Univ., Working Paper Forthcoming, 2022), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4179647.

26 Helee Lev, ESG scores: The good, the bad, & why they matter, Conservice ESG (Mar. 30, 2022), https://www.gobyinc.com/esg-scores-why-they-matter/.

27 Simpson, Rathi & Kishan, supra note 3.

28 Beth Stackpole, Why sustainable business needs better ESG ratings, MIT Sloan Sch. Mgmt. (Dec. 6, 2021), https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/why-sustainable-business-needs-better-esg-ratings.

29 Id.; see also The Aggregate Confusion Project, MIT Sloan Sch. Mgmt., https://mitsloan.mit.edu/sustainability-initiative/aggregate-confusion-project (last visited Sept. 28, 2022).

30 Marjella Lecourt-Alma, Double Materiality: A Matter of Semantics or Substance?, Nasdaq (Apr. 25, 2022), https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/double-materiality%3A-a-matter-of-semantics-or-substance; Matthias Täger, ‘Double materiality’: what is it and why does it matter?, London Sch. Econs. & Pol. Sci. (Apr. 21, 2021), https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/news/double-materiality-what-is-it-and-why-does-it-matter/.

31 Press Release, European Commission, Questions and Answers: Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive Proposal (Apr. 21, 2021), https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/QANDA_21_1806.

32 JP Morgan recently announced a collaboration with software firm Datamaran to provide an AI ESG data analysis tool built on the concept of double materiality. Greg Ritchie, JPMorgan Product Reveals Wall Street’s Shifting Views on ESG, Bloomberg (Sept. 7, 2022), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-09-07/jpmorgan-product-reveals-wall-street-s-shifting-views-on-esg?leadSource=uverify%20wall. This product, the first of its kind in the US market, provides proprietary “materiality assessment models, utilizing data that comes from corporate disclosures, mandatory regulations, voluntary policy initiatives, and online media.” Datamaran, Datamaran Announces Data Collaboration with J.P. Morgan to Deliver AI Driven Technology to Monitor Material ESG Issues, PR Newswire (Sept. 7, 2022), https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/datamaran-announces-data-collaboration-with-jp-morgan-to-deliver-ai-driven-technology-to-monitor-material-esg-issues-301618885.html.

33 Anna Hirai & Andrew Brady, Managing ESG Data and Rating Risk, Harv. L. Sch. F. on Corp. Governance (July 28, 2021), https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2021/07/28/managing-esg-data-and-rating-risk/.

34 ESG Ratings, MSCI, https://www.msci.com/our-solutions/esg-investing/esg-ratings (last visited Sept. 28, 2022); ESG Ratings Key Issue Framework, MSCI, https://www.msci.com/our-solutions/esg-investing/esg-ratings/esg-ratings-key-issue-framework (last visited Sept. 28, 2022); MSCI ESG Ratings Methodology Executive Summary, MSCI ESG Research LLC 3 (June 2022), https://www.msci.com/documents/1296102/21901542/ESG-Ratings-Methodology-Exec-Summary.pdf [hereinafter MSCI Ratings Executive Summary].

35 MSCI Ratings Executive Summary, supra note 34, at 14.

36 Id.

37 Id. at 5–6.

38 Id. at 6–8.

39 Intangible Value Assessment (IVA) Methodology, MSCI 9 (Sept. 2011) (on file with authors).

40 The committee may grant overrides in cases such as when the company has a red flag that it has severely contravened international norms and standards of behavior, a red flag in the ISS Governance Risk Indicators, or has received a top (AAA) or bottom (CCC) rating. Id. at 9–10.

41 Msci Ratings Executive Summary, supra note 34, at 4.

42 Id. at 3.

43 Refinitiv ESG company scores, Refinitiv, https://www.refinitiv.com/en/sustainable-finance/esg-scores (last visited Sept. 28, 2022); Environmental, Social and Governance Scores from Refinitiv, Refinitiv, 56 (May 2022), https://www.refinitiv.com/content/dam/marketing/en_us/documents/methodology/refinitiv-esg-scores-methodology.pdf [hereinafter Refinitiv Methodology].

44 Refinitiv Methodology, supra note 43, at 4.

45 Id. at Appendix F.

46 Id. at 4.

47 Id. at 9, 16–17.

48 Id. at 6.

49 Id. at 7.

50 Id.

51 Refinitiv ESG Scores, Refinitiv, https://www.refinitiv.com/content/dam/marketing/en_us/documents/fact-sheets/esg-scores-fact-sheet.pdf (last visited Sep. 22, 2022).

52 ESGC scores are subscriber-only content.

53 ESG Risk Ratings – Methodology Abstract, Version 2.1, Sustainalytics 4 (January 2021) (on file with authors) [hereinafter Sustainalytics Methodology].

54 Id. at 14.

55 Id. at 5.

56 Id.

57 Id. at 5–6.

58 Id. at 6.

59 Id. at 7.

60 Id. at 14.

61 Id. at 8–9.

62 Id. at 11.

63 Id. at 9.

64 Id. at 12.

65 Methodology Overview, RepRisk, https://www.reprisk.com/news-research/resources/methodology (last visited Sept. 28, 2022).

66 Id.

67 RepRisk Research Scope: ESG Issues, RepRisk, https://www.reprisk.com/content/static/reprisk-esg-issues-definitions.pdf (last visited Sept. 28, 2022).

68 RepRisk Research Scope: Topic Tags, RepRisk, https://www.reprisk.com/media/pages/static/958363135-1657556584/reprisk-esg-topic-tags-definitions.pdf (last visited July 11, 2022).

69 RepRisk Research Scope: ESG Issues, supra note 67, at 1.

70 RepRisk Research Scope: Topic Tags, supra note 68, at 5.

71 Methodology Overview, RebRisk, supra note 65.

72 Id.

73 Id.

74 Methodology documentation, RepRisk, https://www.reprisk.com/lab/reprisk_rating.html (last visited Sept. 28, 2022).

75 RepRisk’s ratings are subscriber-only content—therefore, exemplar ratings for Alphabet Inc. are not provided herein.

76 ESG Scores, S&P Global, https://www.spglobal.com/esg/solutions/data-intelligence-esg-scores (last visited Sept. 28, 2022).

77The Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS®), MSCI, https://www.msci.com/our-solutions/indexes/gics#:~:text=GICS%20is%20a%20four%2Dtiered,to%20its%20principal%20business%20activity (last visited Sept. 29, 2022).

78 S&P Global ESG Scores Methodology, S&P Global 3 (2022), https://www.spglobal.com/esg/documents/sp-global-esg-scores-methodology-2022.pdf [hereinafter S&P Methodology].

79 Id. at 4.

80 Id.

81 Id. at 7–8.

82 Id. at 9.

83 Id. at 4.

84 This reflects the degree of company involvement in the data collection, analysis and review process, and/or qualitative input or signoff on the final rating.

85 Unmanaged risk is the amount of “material ESG risk that has not been managed by a company. It includes two types of risk: unmanageable risk, which cannot be addressed by company initiatives, as well as the management gap. The management gap represents risks that could potentially be managed by a company but aren’t sufficiently managed according to our assessment.” Sustainalytics Methodology, supra note 53, at 11.

86 Idiosyncratic ESG issues are those that “may become significant or material in an unpredictable manner.” Id. at 6.

87 RepRisk collects daily reports from 100,000 public sources and stakeholders, such as news media, social media, blogs, government bodies, and think tanks, in 23 languages and ranging from the international to local level.

88 Huw Jones, Transparency of ESG investment ratings faces regulatory scrutiny, Reuters (Nov. 23, 2021), https://www.reuters.com/business/cop/transparency-esg-investment-ratings-faces-regulatory-scrutiny-2021-11-23/.

89 Rate the Raters 2020: Investor Survey and Interview Results, SustainAbility 13 (March 2020), https://www.sustainability.com/globalassets/sustainability.com/thinking/pdfs/sustainability-ratetheraters2020-report.pdf.

90 “The International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) is the international body that brings together the world's securities regulators and is recognized as the global standard-setter for the securities sector. IOSCO develops, implements and promotes adherence to internationally recognized standards for securities regulation. It works intensively with the G20 and the Financial Stability Board (FSB) on the global regulatory reform agenda.” OICU-IOSCO, https://www.iosco.org/about/?subsection=about_iosco (last visited Sept. 28, 2022).

91 Int’l Org. of Sec. Commissions, Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Ratings and Data Product Providers, FR 09/21, at 24 (November 2021), https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD690.pdf [hereinafter IOSCO, Final Report].

92 Id.

93 Id.

94 Id. at 24–25.

95 Id. at 25.

96 Rate the Raters 2020, SustainAbility, supra note 89, at 23.

97 BlackRock ESG Integration Statement, BlackRock 3 (revised May 19, 2022), https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/publication/blk-esg-investment-statement-web.pdf.

98 Id.

99 Rakhi Kumar, R-Factor: Reinventing ESG Investing Through a Transparent Scoring System, St. Street Global Advisors 2, 5 (July 2019) https://www.ssga.com/investment-topics/environmental-social-governance/2019/04/inst-r-factor-reinventing-esg-through-scoring-system.pdf.

100 See generally CP 21/18: Enhancing climate-related disclosures by standard listed companies and seeking views on ESG topics in capital markets, Fin. Conduct Authority (June 2021), https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/consultation/cp21-18.pdf [hereinafter Consultation Paper, FCA].

101 Id. at 40, 44.

102 See generally Feedback Statement, FCA, supra note 15.

103 Id. at 3.

104 Id.

105 Id. at 5.

106 Id. at 8.

107 Id.

108 See The Code of Conduct for ESG Evaluation and Data Providers (Draft), Fin. Services Agency (July 2022) (Japan).

109 Feedback Statement, FCA, supra note 15, at 14.

110 Letter from Nick Miller, Head of Asset Management Supervision, to AFM Chair, Financial Conduct Authority, Guiding principles on design, delivery and disclosure of ESG and sustainable investment funds, (July 18, 2021), https://www.fca.org.uk/news/news-stories/guiding-principles-on-design-delivery-disclosure-esg-sustainable-investment-funds.

111 Consultation Paper, FCA, supra note 100, at 34.

112 Feedback Statement, FCA, supra note 15, at 13.

113 Press Release, European Securities and Markets Authority, ESMA Launches Call for Evidence on ESG Ratings, (Feb. 3, 2022), https://www.esma.europa.eu/press-news/esma-news/esma-launches-call-evidence-esg-ratings.

114 Consultation, European Commission, Targeted consultation on the functioning of the ESG ratings market in the European Union and on the consideration of ESG factors in credit ratings, https://finance.ec.europa.eu/regulation-and-supervision/consultations/finance-2022-esg-ratings_en (last visited Oct. 7, 2022).

115 Press Release, ESMA, ESMA Publishes Results Of Its Call For Evidence On ESG Ratings (Jun. 27, 2022), https://www.esma.europa.eu/press-news/esma-news/esma-publishes-results-its-call-evidence-esg-ratings.

116 Proposed Rule, Enhanced Disclosures by Certain Investment Advisers and Investment Companies about Environmental, Social and Governance Investment Practices, Rel. No. 33-11068 at 12–13 (May 25, 2022) (available at https://www.sec.gov/rules/proposed/2022/33-11068.pdf) [hereinafter, SEC Proposed Rule]. The comment period for the SEC Proposed Rule closed on August 16, 2022 and are publicly available. See generally Comments on Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosures for Investment Advisers and Investment Companies, Rel. No. 33-11068, US SEC (last updated Sept. 2, 2022), https://www.sec.gov/comments/s7-17-22/s71722.htm#comments.

117 Id. at 199–202.

118 ESG Disclosures for Investment Advisers and Investment Companies, U.S. SEC, https://www.sec.gov/files/ia-6034-fact-sheet.pdf (last visited Sept. 29, 2022).

119 SEC Proposed Rule, supra note 113, at 46–47, 241.

120 Press Release, Toomey Asks ESG Ratings Firms For Info on Scores, Data Collection Practices, U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, (Sep. 21, 2022), https://www.banking.senate.gov/newsroom/minority/toomey-asks-esg-ratings-firms-for-info-on-scores-data-collection-practices.